Today’s youth are physically weaker than previous generations, and a vast majority are not accumulating at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day. Despite public health guidelines that recognise the potential physical, psychosocial, and cognitive benefits of regular physical activity only 1 out of 5 adolescents meet international physical activity recommendations. Measurable reductions in physical fitness are emerging, sport participation rates during adolescence are declining, and the medical and financial burden of activity-related injuries in children are substantial.

A Developmentally appropriate approach that recognises the foundational importance of the various components of fitness is crucial towards creating physically literate young people with a confidence and competence to take part in physical activity or sport throughout their lives before they become disinterested, disengaged, and disconnected. Getting this right is an essential building block in our efforts to encourage a healthy active nation.

What is the best approach to take?

There have been a number of training and development models created over recent years to show activities and training children should do at each stage of their development each with their own merits.

Perhaps the most popular and well-known model is the Long Term Athlete Development framework from Canada which is structured around growth and maturation timepoints, rather than chronological age determined points. The LTAD model is a seven-component framework starting at 0-6 years entitled Active Start and introduces basic movement skill development, and then moves onto fundamentals, learn to train, and then train to train, train to compete, train to win and active for life.

The LTAD framework was intended to produce a long-term approach to maximising individual potential and involvement in sport and physical activity, although it was criticised for an overreliance on ‘optimal windows of trainability’ and was seen to be too one-dimensional by focussing too heavily on the physiological aspects of performance, rather than considering other psychological, social, or academic factors. The LTAD model was adopted by a number of sporting organisations.

Another popular development framework was the Developmental Model of Sports Participation which advocates early, playful and non-specific specialisation up to 6 years of age. From the age of 6 years to 12 years, there is a promotion of a variety of sports without a focus on any particular specialisation. From the age of 13 years to 15 years a reduced variety of sports is played and from 16 years onwards there is a greater investment in a single sport. In particular for team sports, children are encouraged not to engage in any one specific sport until at least age 13-15 years. The model also highlights the particular role an influence of coaches, parents, schools, and peers.

You may recognise this model as something similar to one lot’s of children are currently taking, but one of it’s weaknesses is that it’s not suitable to apply to such sports where specialisation and sporting achievement occur at an early age like gymnastics, diving, or figure skating.

Given that there are concerns about the potential negative outcomes of early specialisation, including high rates of injury and drop-out, this framework where children are exposed to a diverse range of motor skills from a young age rather than learning a narrow skill set from specialising early in a single sport may be a good idea.

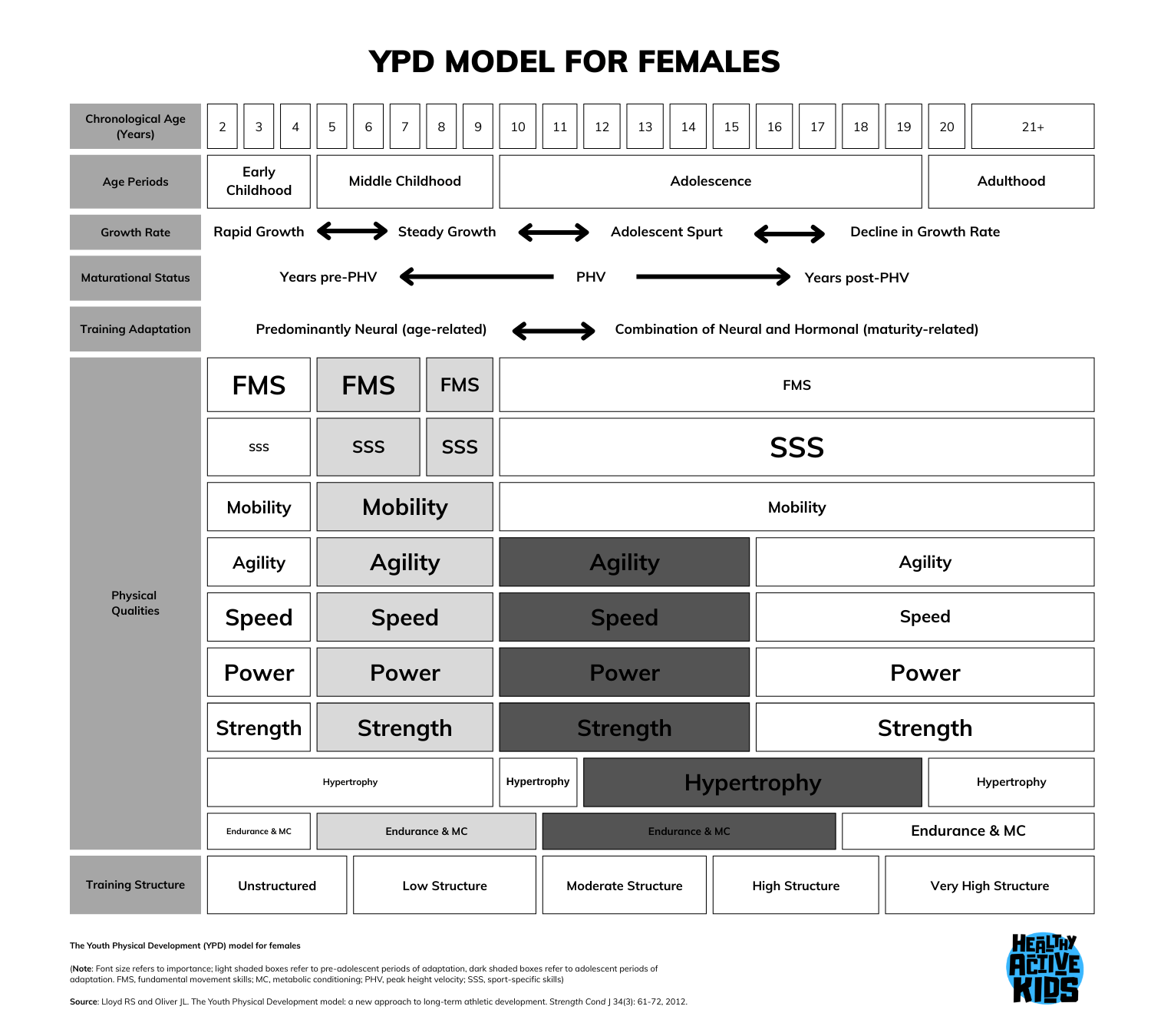

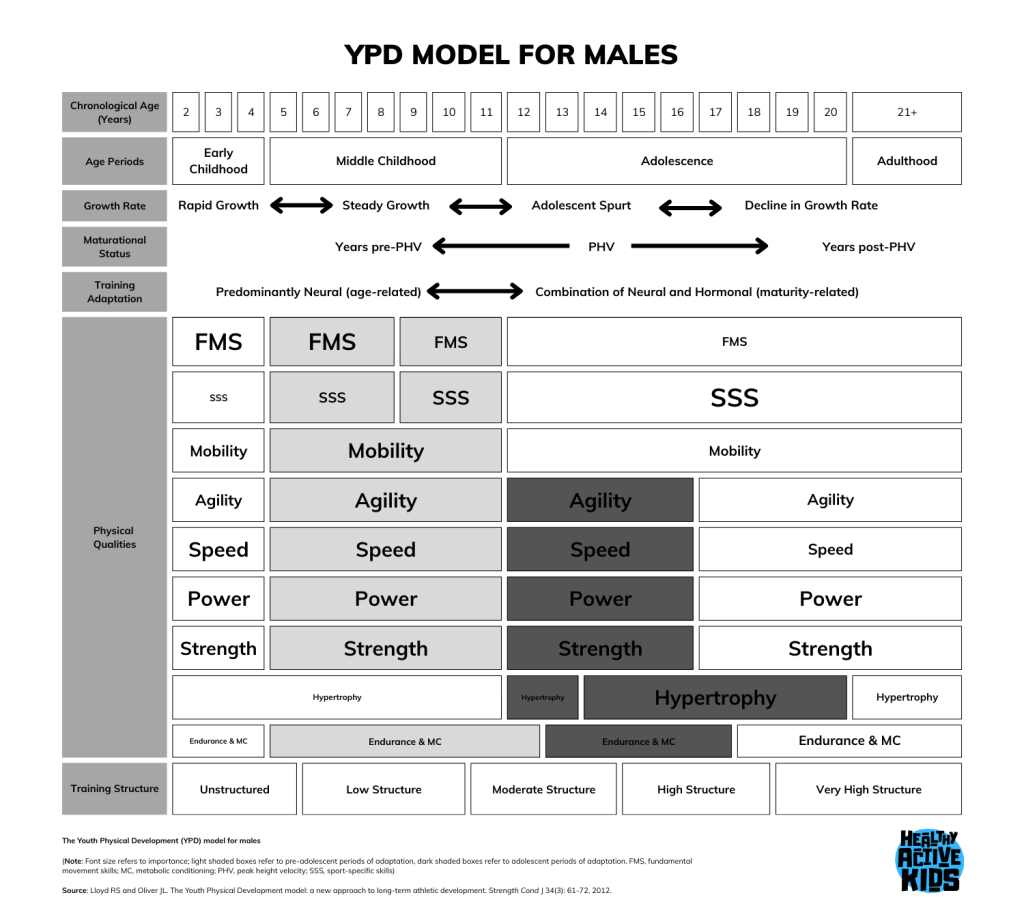

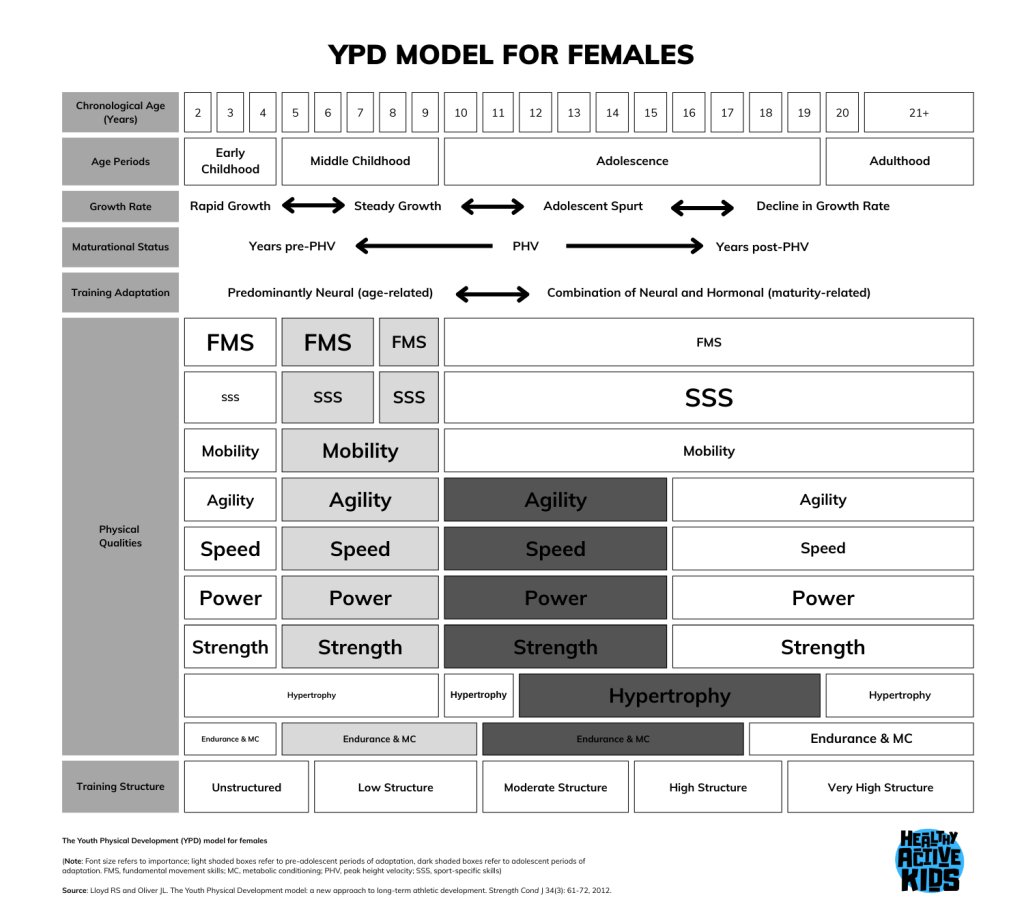

Perhaps the most specific framework is the Youth Physical Development model, which is a contemporary model for developing physical abilities throughout childhood. Similar to the long term athlete development model the Youth Physical Development model highlights the importance of considering training with respect to the maturational status of children, identified by the timing of peak height velocity. However, the Youth Physical Development model moves away from the concept of opportunity to the position that most components of fitness are trainable, irrespective of the stage of maturation, although the mechanisms that underpin training adaptations are likely to differ between the childhood and adolescent years. It suggests that before adolescence, training adaptations will have a predominantly neural basis, whereas, once puberty has been reached, adaptations may be stimulated by the increase in hormone levels.

The Youth Physical Development model recommends the type of training that may best suit the individual depending on their stage of maturation. For example children who have not experienced their growth spurt respond more positively to plyometric training which encourages neural adaptations and skill development, whereas children following their growth spurt respond more to traditional strength training.

Due to the individual timing and tempo of maturation, and with girls tending to experience their growth spurt earlier than boys the Youth Physical Development model provides a framework for both boys and girls respectively. It highlights that all components of fitness are trainable to some degree throughout childhood, with font size indicating the importance of each component during different periods of childhood.

Central to the model is a large emphasis on the development of muscular strength and movement competency throughout both childhood and adolescence. These are both associated with higher physical activity levels, improved health and wellbeing, and reducing the risk of activity related injury and are viewed as the major fitness commodities within the Youth Physical Development model.

Summary

So a number of different models of long term development exist, each with a predisposition towards a particular scientific domain. A multidisciplinary approach that considers physiological, psychological, sociological and educational development may be the most difficult but rewarding approach to take.

Any long-term development programmes should aim to retain as large a pool of children as possible to ensure as many people maintain a relationship with sport or physical activity as they get older. Long-term programmes should start early, build the foundations of movement competency and strength, provide a variety of training stimuli, progress based on competency, but also consider the role of maturation.